Over the years, what stands out in my memories of our family Thanksgiving dinners is that they were remarkable for their lack of drama.

In the years before Martha Stewart made everyone feel guilty for not creating memorably lavish gastronomic triumphs, Jack and Giffy Marshall did a pretty good job of creating memories for me with the small core group of regulars who each year came to our house on Audubon Place in Shreveport to give simple thanks.

In my recollection, there was nothing outrageous enough to make into a movie, or even into a sitcom script. No breathtaking revelations from family members, no drunken brawls amongst aunts and uncles, no unruly dogs eating the turkey from the kitchen counter. Nothing but good food and a larger than normal group around the table.

Don't get me wrong though. Thanksgiving at the Marshalls always was a special day, and I looked forward to it as a highlight of each year of my young life.

First was the food itself. Not so much the quality -- although our mother was an excellent cook -- but the quantity. The Marshalls were neither poor nor rich. But, on the 364 regular days of the year, there were limits imposed on what we could eat and drink. ONE slice of bacon and ONE glass of orange juice at breakfast. (There was a lot of bartering, however, between siblings.) Lots of spaghetti and casseroles. Salmon croquettes or fish sticks on Friday. Roast beef with rice and gravy once a week, on Sunday. Few snack foods or desserts.

Thanksgiving was just the opposite. There was a full and diverse menu from which to choose and plenty of everything!

Most memorably, we ate in the dining room, not the kitchen. Mom and Dad made a big deal out of putting the large oval top on the dining room table, which made it big enough for 12 or more. If the crowd was particularly large, a series of card tables was attached from the bottom of the oval, and stretched into the living room area. Thanksgiving was the one meal a year when we ate off the "good china" with the "real silverware." And thanks to Land O'Lakes and the A&P Supermarket, there always was "real butter" too -- an unheard-of treat!

Another thing that was special about Thanksgiving to me was that there usually was no kids table. My sister Mary says Giffy wanted it that way, for everyone to sit together. I always liked that. Even when I was small, I remember sitting with the grown-ups and listening to grown-up talk, about President Kennedy, maybe, or the new Pope who had changed the rules regarding fasting before communion, or whether Navy could beat Army in the week's big game. My mother's mother, Mere, had a favorite expression from growing up in a large, multi-generational, French-speaking home. "Let only six talk at a time," Mere would say, and at our Thanksgiving table, that often was the case.

When all was ready, Jack Marshall would begin the blessing. Nowadays, we usually improvise, with one person or everyone giving specific thanks for the many blessings in our lives. Back then, Dad's leadership was limited to saying the familiar first words, "Bless us oh Lord..." and then we'd all join in, "and these thy gifts, which we are about to receive from thy bounty, through Christ our Lord. Amen." It was the same blessing we said every day, for every meal, but on Thanksgiving, we recited those well-known words with special fervor. For on that day, the word "bounty" really meant something.

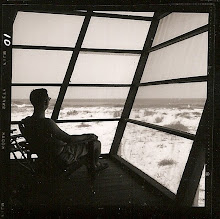

The pictures with this post were taken 39 years ago today, on Thursday, November 26, 1970. When I saw the date noted on the back of Jack Marshall's contact sheet, I was amazed that Thanksgiving fell on the same date, November 26, as it does this year. I checked an online calendar to make sure it was true!

Before the meal, everyone trooped out front for Dad to take our picture: Mom, my brother John, and my sister Mary, with only brother David missing; Mere, and my father's mother, Catherine; my father's sister Doris and her husband Harry (in his Navy uniform), along with their daughter Patty and her husband Bill, and Catherine's sister, Blanche. I believe I took the other picture, of Dad, just before he began carving the turkey, with a happy Mere to his right and his mother Catherine to his left. Dad always made a big show of honing the knife to its sharpest just before starting to slice.

There are so few pictures of Dad -- since he usually was the one behind the camera -- that I really love this photo. Even though he is giving me a big, cheesy pose, I think I can see the twinkle in his eye and his true joy at being surrounded by his family. He is not quite 50 years old, in the very prime of his life.

Less than 6 years later, Jack Marshall was gone.

If he were still alive today, we could be celebrating Thanksgiving dinner with a crowd including his 4 children (and spouses), 11 grandchildren -- many of them now with spouses, and even a couple of great grandchildren. There could be 30 or more around the table, and I bet Dad would still be leading us in "Bless us oh Lord" before proudly carving the turkey. I'm sorry Dad died without ever sharing that huge Thanksgiving feast. There might have to be a kids table now, and there definitely would be even more food.

And I'm very certain Jack Marshall would have taken the definitive photograph of the assembled group, because that's what he always did. He would have enjoyed this day immensely.

Today when I give thanks for the many blessings in my life, I will, as I always do, say a silent prayer of gratitude for our heroically normal, quietly loving father, Jack Marshall. For he gave us the gift of a happy, secure, wonderful family, his forever legacy to us all, a gift of infinite, inestimable value.

Happy Thanksgiving everyone!

--Tom Marshall, New York City,

Celebrating Thanksgiving 2009 in Seattle

Celebrating Thanksgiving 2009 in Seattle