For my 10th birthday, I had just one request. I wanted my father to take me fishing.

For my 10th birthday, I had just one request. I wanted my father to take me fishing.I had it all planned. This was not going to be fishing with a cane pole from the bank of the bayou a block or two from our house. Heck, that would've been too easy. My best friend Patrick Grant and I – along with almost every other kid in the neighborhood – fished by ourselves in that bayou all the time. We didn't consider that "real" fishing though.

For real fishing you needed a real rod and reel. And a real tackle box. And a real lure, not a worm or cricket or scrap of bacon on a hook. Most of all, you needed a boat.

The rod and reel were easy. For months, I had pored over the slick color advertisements in Boys' Life Magazine and I had found the perfect gift. The ad promised that, in exchange for $10 plus a small amount for shipping and handling, you would receive a 100% genuine grown-up "fishing kit" that virtually guaranteed huge fish would be jumping into your arms. The kit featured a rod and reel, a collection of lures, and a hunter green tackle box.

I must've done a pretty good sales job that year, because on my birthday, February 10, 1964, my father proudly presented me with the fishing kit I had seen in the magazine ad. The rod was tiny – it looked like it was made for a 3-year-old – and the lures were poor imitations of the shiny, multicolored "H&H" lures we kids had spent hours examining near the check-out counter of our local Pak-A-Sak convenience store. Worst of all, the tackle box was a cheap-looking, diminutive plastic case not much larger than a size 3 shoebox.

I tried to hide my disappointment. Still, it was exactly what I had requested, and I remembered the smiling boy in the ads. We could make this work. My father had spent ten whole dollars on this gift, and I was not about to appear ungrateful.

Since my birthday occurred in what passed for mid-winter in Louisiana, the actual fishing trip was scheduled for a time when the weather turned warmer.

Finally, the day arrived. May 17, 1964. It was a Sunday morning, 3 days after Dad's own birthday, his 43rd.

The night before, as I was carefully preparing my clothing and gear for what was sure to be the greatest triumph of my young career as an outdoorsman, my father asked me what time people were supposed to leave for a real fishing trip. I had heard that fish were hungriest when they just woke up, so I guessed 4:30 a.m. Dad grimaced and suggested 7 o'clock. We compromised, as I recall, on 6:00. The next morning, we were up early. As we quickly ate breakfast, Giffy packed tuna salad sandwiches and fresh fruit for our lunches.

And then we were off on our grand adventure.

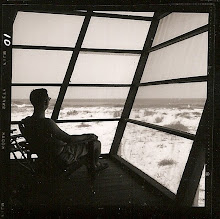

Dad drove north from Shreveport on Louisiana Highway 1. We passed through the barely awake towns of Blanchard and Mooringsport. We crossed a low bridge on the edge of our destination, Caddo Lake – a huge body of water which straddles the border between Louisiana and Texas. Caddo Lake, named for the Native Americans who lived in the area beginning in the 16th century, is reportedly the largest freshwater lake in the South and home to the largest cypress forest in the world. Of course Jack Marshall had his camera, and when we arrived at the small marina in Oil City, he took a moment to frame the photograph at the top of this entry, just as the sun began to peak through the huge old cypress trees.

Now it was time for some serious fishing. Dad paid our rental fee, and I clambered down into the little aluminum row boat. He snapped one more photo, the one of me smiling through my thick glasses (my 10th year may have been the absolute peak of my geekiness, as you can see in the photo at the beginning of the article). When I found this photo recently, I shouted out loud, "Oh boy!" There was no one to hear my shout, but I was overwhelmed because I did not know this photograph even existed. Looking into my own face, eyes and smile from a time more than 45 years ago recreated in me the very same feeling I had at that very moment: absolute, pure, boundless, giddy joy.

And then, we shoved off into the still, black waters of Caddo Lake. The intrepid fisherman in me entertained visions of huge fish, mounted forever on the wall of my bedroom. Dad allowed me to select the first fishing spot. Miraculously, the little fishing kit functioned perfectly, and soon my lure was in the water. Dad had a rod and reel too, and he tried his hand. Alas, this spot held no luck for either of us. We moved on to another quiet corner of the lake, and then another. Not even a nibble. By 9:30, we were eating the sandwiches, and talking quietly. Man to man (sort of). Like fishing from a boat, this too was a new experience for me. By 11, with no fish in the boat and running low on food, we headed back to the marina. We were home by noon.

Rather than being disappointed, though, I was satisfied. We had given real fishing a try. We had bonded as father and son. Looking back, I realize now Jack Marshall had given me the most valuable gift of all, his time. In the process, he taught me some important truths about parenting – that a child's dream is important to follow, even if the reality doesn't quite live up to the hope. That sometimes just being there is truly the best gift. And that you can say "I love you" in actions as well as in words.

It was, without any doubt, the greatest day in my young life.

– Tom Marshall, New York City