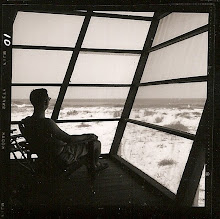

It is the most iconic photograph in The Jack Marshall Collection™.

This photograph (above) of San Francisco Plantation, on the Great River Road near Garyville in St. John the Baptist Parish, Louisiana, was captured by Jack Marshall sometime in late 1958 or early 1959. This breathtaking home, built in 1856, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. It certainly is one of the most distinctive of the dozens of plantation homes that dot both sides of the lower Mississippi River.

According to the plantation's web site, the home's unique architecture, viewed from some angles, closely resembles the "ornate yet graceful superstructure of a Mississippi riverboat." It is the inspiration for the novel "Steamboat Gothic," written by Frances Parkinson Keyes about a family she imagined lived there.

Earlier this year I investigated Jack Marshall's darkroom at my mother's house in Shreveport for the first time in the 33 years since his death in 1976. The process of discovery was amazing and fun, as each cabinet and drawer revealed new treasures. Now as I study and organize the many prints my father so lovingly printed, annotated and stored, the many variations of this photograph have emerged as possibly the most often printed image of Dad's work.

That's why I selected "Steamboat Gothic," as Dad titled his work as well, to be the home page image on the main web site of The Jack Marshall Collection™ (www.jackmarshallcollection.com) which is launching this week.

To me, this remarkable image of a well-known South Louisiana plantation house is not only one of the best examples of my father's artistic talent, but also provides a perfect insight into how he worked. Another view from below the steps is published at the end of this entry. The key to understanding how Jack Marshall worked can be found in the detail of my sister Mary, somewhere around 2 years old, determinedly toddling her way down the plantation's grand staircase.

If Mary was 2 years old at the time of this photo, I would have been about 4. And although I don't remember the exact circumstances surrounding the trip during which Dad created this image, it doesn't matter. Because the Marshall kids were usually there when Dad was making photographs.

That's the point of this entry.

Jack Marshall almost always had a camera -- or two -- around his neck. Of the thousands of photographs which I am now organizing, a huge percentage are images of my mother, brothers, sister, aunts, uncles, cousins, classmates and friends. But while he was taking our pictures, he also always was looking up at the big world around us. And then turning the camera in other directions, for many remarkable, memorable photographs.

By the time Dad took the family out West for our camping adventures, we were totally accustomed to the many extra photo-taking stops along every road, hike, dam, beach, picnic and tour. The memories of all of those places come flooding back to me as I study the tiny images on hundreds of contact sheets, the small index prints of each roll of film my father shot and developed and filed away. Inevitably, there are pictures of Mary and me, or John and David, or my mother, or all of us, standing in front of a National Park entrance, or a motel restaurant, or a "Welcome to Colorado" sign, or a quiet campground or frightening canyon rim. And on those same sheets of tiny family photos often I find stunning images of soaring mountain peaks, roaring rivers, heart-stopping valleys, and sunsets so beautiful I want to cry.

I was there with my living, breathing, happy-in-the-moment Dad, I remember again. I was there when he would say to us, waiting in the car, "Just one more minute." While he watched through his tripod-mounted camera for just the right moment and light to get the photograph he envisioned. Dad was with his family, taking photographs, in his element, doing what he loved most.

I was there once. And through The Jack Marshall Collection™, now you can be there too.

- Tom Marshall, New York City